Book & Film Review

This week, I review a book by Oğuz Atay, a writer I love to read, and a movie by director Nehir Tuna, who is a also fairly new name for me.

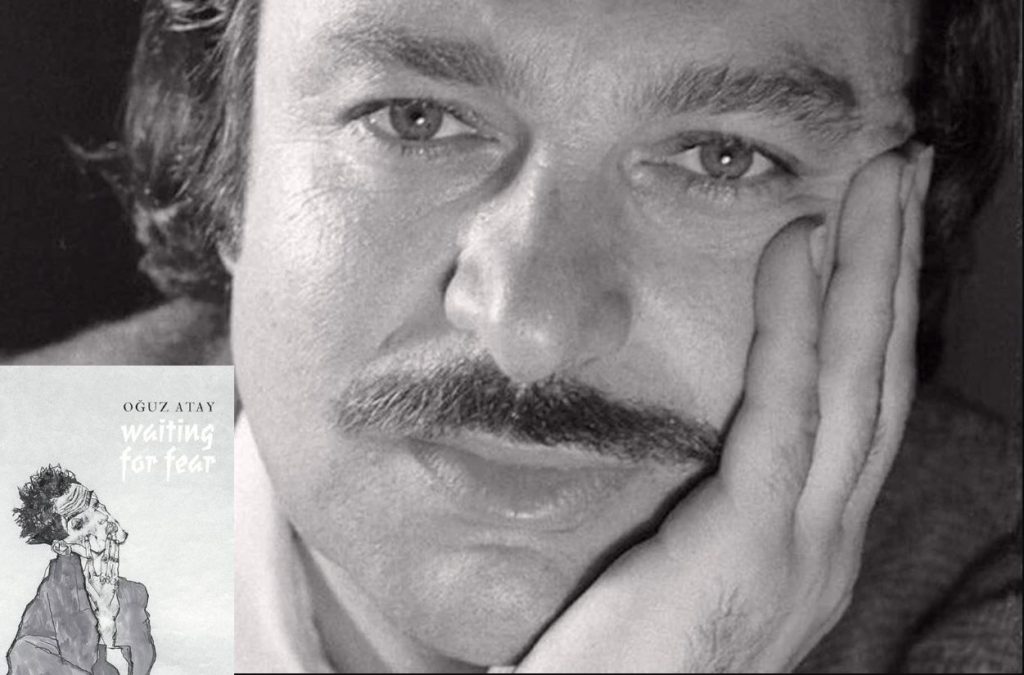

Oğuz Atay – Waiting for Fear

Waiting for Fear, which consists of compiled stories, was first published in 1975. It was first translated into English by Fulya Peker in 2021. The book was translated into English again by Ralph Hubbell this year with the same name.

The author’s only short story book, Korkuyu Beklerken, whose books can be evaluated in post-modern literature, consists of eight short stories. I think this is the best book to start Oğuz Atay’s literature and to understand his language. Drama and tragedy, as well as humour and sarcasm, constitute the main features of the language in the stories.

The common feature of the characters in their stories is that they are laughable in the dramatic events in which they are stuck. In some of his stories, the element of drama is more dominant, while others approach more sarcasm.

Another feature of the characters is that each of them is lonely. These people are outside of society, unable to blend in with the crowd and feel alone. The loneliness of the characters is sometimes conveyed by depicting them in pathetic-ridiculous situations, or it is transmitted in realistic language that makes them feel helpless.

In the first story, “The Man in the White Coat” (story names may differ in translated books), we read how a man dressed in a woman’s coat, who does not speak at all, is dragged from place to place in the back streets of Istanbul and eventually exhibited in a shop window to be used as a lifeless mannequin.

In the story “Unutulan”, Atay writes a text in a woman’s language for the first time. In this very successful attempt, we read about the astonishment of a woman who comes across her ex-lover whom she forgot in the attic.

These two stories are striking and hard stories in which drama elements are used very successfully in the language. While providing this punch, Atay does not compromise on the colourfulness of his language.

Contrary to these, we can give an example of the story “Ne Yes Neither No” as an example of a story with high humour and sarcasm. Our character, a young journalist, is making fun of one of the readers’ letters that came to the newspaper. In this story, we read the ineptitude and stupidity of a young lover through the eyes of a journalist.

Although Atay’s language is generally simple and understandable, the fact that he plays with words frequently uses the stream-of-consciousness technique and likes to play with the structure of the texts makes his novels difficult for some readers. However, his stories generally have a certain rhythm and fluency.

In the articles I read about the English translations of the book, the Turkish translator Fulya Peker considered it a true translation because of the decision to preserve Atay’s “language quirks”. From the reviews of Ralph Hubbell’s translation, I sensed it was more suitable for native English speakers. However, reviews are generally positive for both translations.

It is a difficult task to use the most accurate English and to preserve the originality of the author’s language. I think it would be a good idea for readers who are curious about Atay to compare the two translations.

Nehir Tuna – Yurt

Yurt, one of the two Turkish films screened at the Venice Film Festival this year, is Nehir Tuna’s first feature film. I can easily say that Tuna, who is a director I watched for the first time, left a positive feeling in me.

“Yurt” focuses on Ahmet, a fourteen-year-old high school prep student living in a religious dormitory. The film, which is about Ahmet’s struggle for freedom and his being stuck between school and dormitory, trying to meet the expectations of his father, who has recently turned to religion, tells a story of growing up in the politically polarization atmosphere of Turkey in the late 90s.

Ahmet’s search for belonging is discussed in the context of Turkey’s division between secularism and religiosity.

Ahmet finds himself in sexual, ideological and emotional dichotomies throughout the film. Although political and social references and phenomena are frequently used in the film, the desire of a young person to connect to the world and to a person is the main focus of the story. In this respect, although references such as Atatürk posters and television news about religious sects are included in the film, none of them are used to produce a discourse. All of this appears to be reduced to a mere instrumental dimension.

Many scenes in Yurt contain references to Turkey’s 90s. Ahmet’s journey with Hakan, his friend from the dormitory, is also full of references to the period. However, these references are given without deepening. This makes it feel like something is missing that needs to be said throughout the movie.

However, for foreign viewers, not deepening the references in the film may have made it more understandable and relatable.

The relationship between Ahmet and Hakan was brought to the screen in a very impressive and sincere way with the performances of young actors Doğa Karakaş and Can Bartu Arslan. The growing closeness between these two young people is consciously emphasized in small moments where body language comes to the fore instead of words.

These scenes can be interpreted as homosexual images that create sexual tension between our characters. However, the fact that Ahmet, who was growing up, stayed in a dormitory full of men may have led to his first discoveries about sexuality in this way. The director consciously leaves the interpretation to the audience.

Changing the colours in the sequences is a technique often used in cinema to highlight the change in a character’s mood or perception of the world. It’s even a bit of an outdated technique. However, I can say that it doesn’t seem inappropriate at all in the movie.